Missional Movement Through the Local Church: Applying Movemental Principles in a British Context

by Rev Dr Nick Allan

Research Findings

What common practices are foundational in creating a culture of missional movement through a local church?

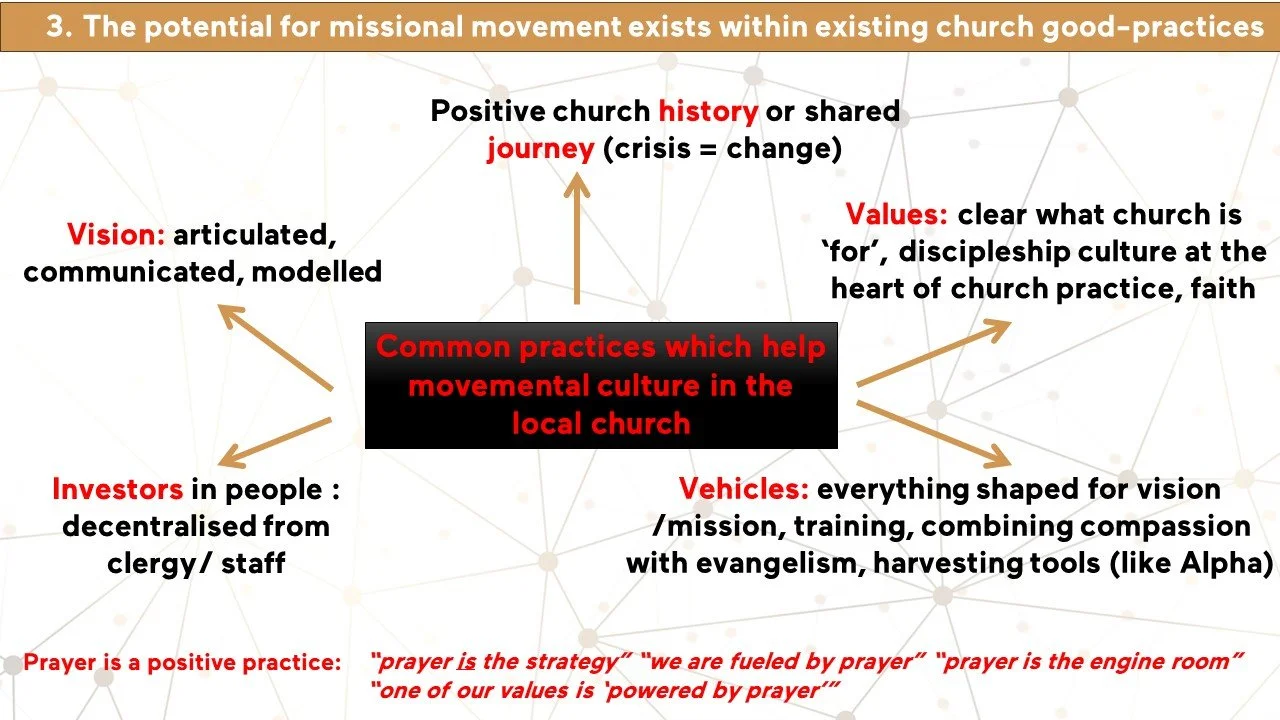

Research and analysis shows that The potential for missional movement exists within existing church good-practices.

1) A Church’s History and Shared Journey

Church leaders referred to three distinct patterns which contributed to creating a culture of missional movement within their local church.

1. The positive missional heritage of a church’s history and previous culture. This had the positive effect of the right ‘DNA’ being part of the church for a long time, which created its own sense of momentum and expectation.

2. The impact of the church body coming together in reaction to negative circumstances, such as decline, with renewed clarity and passion. The key seems to have been that the congregations and leadership teams then took great ownership of the necessary response and were willing to make changes in their common church practices to achieve their newly focused goals. One leader explained “we are going through a re-birth, re-structure and reform in the church. The previous leadership had a model that is best described as all roads lead to them, this created a bottle neck dynamic to all things. We are trying to re-establish and grow away from this”.

3. The impact of the COVID19 pandemic was a driver for change, both positively and negatively, in many churches. A large number of leaders identified it as a significant hindrance by disrupting their previous patterns of attendance and engagement in ministries. However, others utilized the disruption to pioneer new mindsets and methodologies. In one case, the church had been gradually exploring DMM methodologies, and the conditions of lockdown were a trigger: “I think it linked-in with the way people were feeling coming into COVID. One of our leaders said, please, can we not go back to doing what we did before?”

2) Vision and Vocabulary

The in-depth interviews with senior leaders of local churches emphasized as foundational the fact of churches, of whatever type and size, having a clear vision, which was consistently communicated using simple, memorable vocabulary and then modelled to congregants by influential leaders. The primary tool which virtually all twenty interviewees mentioned was that of telling stories and sharing testimonies which demonstrated the church’s vision in practice. Often it was the examples of early adopters who were exemplifying the missional vision. It was evident that a church’s senior leader had a key role in making change happen by projecting the vision through their passion, belief and practice. One described the senior leadership role as two-fold: “there’s the training and trying to give an ongoing commentary on what’s happening, what’s working, setting the vision; as well as giving people skills”.

3) Values

A key factor related to what best-practice churches valued, meaning their implicit ecclesiology and their conception of church itself. It can be summarized in three categories:

1. Ecclesiology, whereby they had a clear conception of ‘what is church for’.

Those who favoured a gathered, inherited model of church exhibited a strong confidence that the organized entity of the local church was a potent force for the multiplication and growth of the kingdom. Their examples centred around organized ministries, leadership training, and the both/and value of gathering and dispersing as the body of Christ. Several described the purpose or trajectory of their church as operating like a central hub that would nurture and send out missionary disciples and church plants.

In contrast, leaders of dispersed micro-churches based around small relational-based groups valued the local church as a covenant body to belong to and strongly commit to, and as an organic entity which must facilitate multiplication beyond the traditional confines of the Christendom ecclesial models. They emphasized a key value in coming together in small-to-mid sized groups for the dual purpose of fellowship and to foster accountability for outreach in everyday-life, which they called ‘obedience-based discipleship.’ They placed a high value in principles of flatter leadership structures and of low maintenance/high mobility. At either end of the spectrum, leaders from macro and micro-church spoke in RI2 about the importance of making their gathered times accessible so that non-Christians could easily engage with them.

2. Creating a culture of missional discipleship within all their congregants.

There were three key features of this focus upon discipleship: a culture of intentionality; training and resources to support it; and a focus upon equipping every person towards whole-life discipleship, to be equipped to deliberately express their faith and witness in all circumstances of life. Best practice churches were committed to achieving a conceptual shift from a more passive congregation towards equipping every person to view themselves as missionaries in their contexts.

3. The place and practice of faith.

Interviewees observed a significant link between a church culture with high faith expectations and levels of confidence and courage within the congregations, and proportions of people coming to faith. The place of prayer was also vital. These observations tally with what missiologists say is a key driver of Church Planting Movements and Disciple Making Movements: high levels of faith and evidence of the supernatural (Trousdale et al. 223–36).

4) Vehicles

An intentionality of vision and values was translated into specific methodologies and ministries designed to achieve their aims. These may broadly be described as the “vehicles” or methods through which a church sought to achieve its objectives. Five observations:

1. Intentionally Shaping Practices to Achieve a Missional Vision and Values

The rhythm and style of Sunday gatherings was modified by those churches focused on hybrid and micro-church models, typically reducing their frequency away from a weekly occurrence. This was a deliberate attempt to embed missional practices within their congregants which took them away from the conventions and habits of the inherited-church model.

In the role of their staff and leadership teams, those leaders focused upon multiplication viewed their roles primarily as missional coaches, rather than the more traditional ‘pastor/teacher’ model.

2. Training

Missional churches shaped their practices through a heavy emphasis upon training. There was a notably higher positive response rate from best-practice interviewees regarding measurable training principles and practices, when compared to the survey averages. For example, in the survey a relatively low figure of 44% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed with the statement “my church raises leaders rapidly into the discipleship of others, both within and beyond formal church structures/ministries”, compared to 95% of interviewees. In the whole survey the majority of responses leant towards a view of discipleship as primarily a person reaching Christian maturity and engaging in some kind of service in or through church ministries. In contrast, best-practice leaders gave examples of training which was geared beyond personal maturity or spiritual disciplines towards a missional lifestyle and whole-life discipleship.

3. The significance of a building or a regular presence/place in the locality.

Best-practice churches made strong use of their premises for missional purposes and the connections they generated with local people, including the attraction of a powerful worship experience, ministries to serve the poor/vulnerable, or welcoming café spaces.

4. Avoiding Bifurcation

Bifurcation is the intentional separation of works of compassion to the poor and vulnerable and works of evangelism. This was always a deliberate action.

5. Harvesting Vehicles

Another common vehicle was that most growing churches utilized packaged courses such as The Alpha Course or Christianity Explored which they reported working as efficient harvesting vehicles in bringing new people to faith, and crucially, in developing mission-minded disciples.

5) Investing in people

A common factor in creating a culture of missional movement through a local church was how much churches invested in their people in addition to training. Leaders often described investing in people to build up their confidence in themselves, the gospel and in sharing or expressing their faith publicly.

In RI2 best-practice churches there was a deliberate decentralization away from the clergy or staff teams. These people still important played roles, but they tended to be more as mission enablers, seeking to raise and empower vision, vocation, passion and initiative in their congregants to live as whole-life disciples. When asked about where power and authority lay between the clergy/staff (45%) and the laity (45%), there was an aggregated even split (S2Q34). Notably, this second category was higher than the RI1 survey average of 33% towards the laity

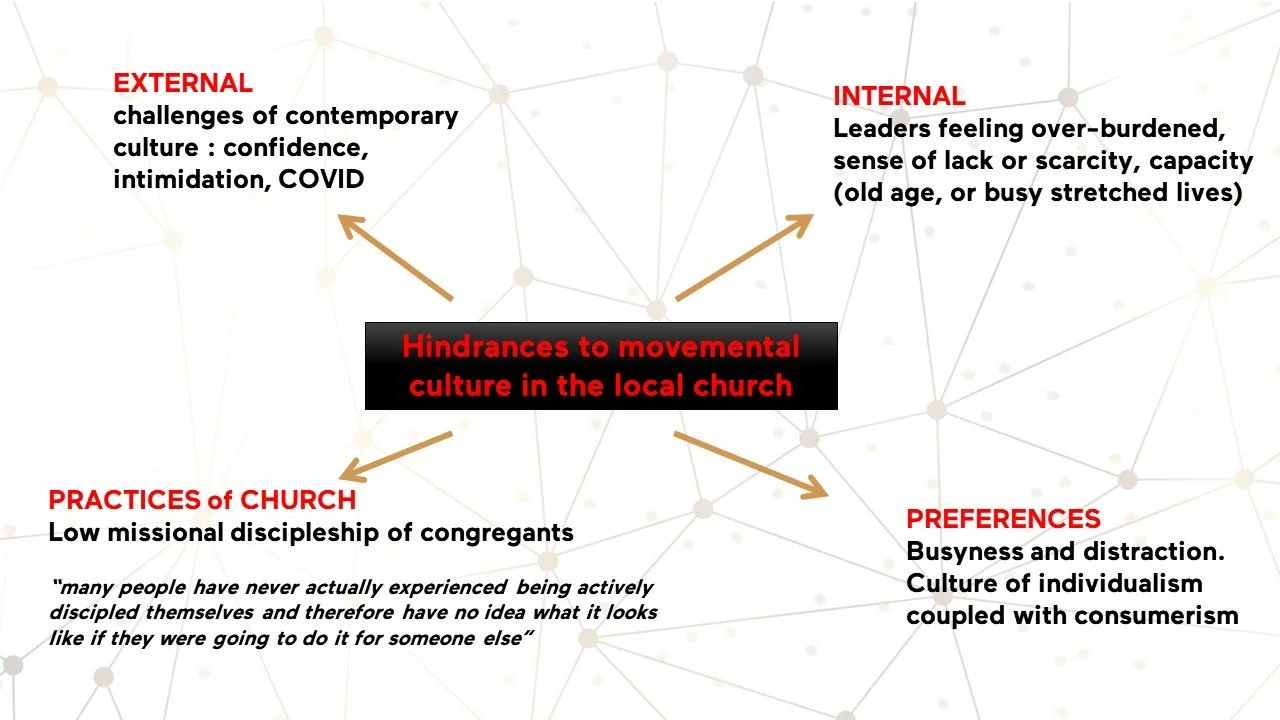

What common practices hinder a culture of missional movement through a local church?

Research Question #2 sought to evaluate the common obstacles which practitioners identified as foundational in creating a culture of missional movement through a local church.

1. External factors

a) The Challenges of Contemporary Culture

Confidence was a key theme. It was the view of church leaders that Christians often had a lack of confidence in themselves and their ability to share the gospel, sometimes due to a lack of personal courage. They described a fear of speaking out due to a feeling of intimidation, a hesitancy to impose their Christian views in friendships or work relationships for fear of seeming arrogant or offensive by broaching views which were seen as contentious or taboo. Several leaders suggested people had a lack of confidence in the gospel itself and that low biblical literacy was a factor. Others reflected upon how people feel they have a lack of tools, or they don’t know how to share the gospel.

A survey respondent summarized,

“The British Church, my church, has lost its sense of adventure, lost its willingness to do a Peter and step out of the boat, lost its expectation that God still saves people, God still heals people, God still performs miracles, God is still able to transform cultures and communities”.

Another challenge of contemporary culture identified as a hindrance was “helping those in the church to navigate a changing world” . Several leaders commented that the recent immigrants within their church, or their older age congregations, “just don’t get” the contemporary post-Christendom context of the UK, and so do not understand how to engage people evangelistically or appreciate some of the cultural debates. Several mentioned the bewildering impact of contemporary “culture wars” and numerous leaders referenced society’s views on human sexuality as areas of contention which left Christians feeling marginalized by society or under-equipped to engage missionally.

b) Impact of COVID19 and the UK lockdowns between 2020–2021.

Many respondents identified significantly lower patterns of attendance at church and engagement with church ministries since the lockdowns. One leader reported that around thirty percent of their congregation had never returned since lockdown . Several others discussed how lockdown had broken their church’s previously regular meeting rhythms and structures, and that they had struggled to re-establish them since. They observed a greater desire for stability and inward fellowship within their congregations and a surge in the demands of pastoral care upon the church staff, which was diverting the whole church from missional momentum.

c) Cultural Baggage within UK Society about ‘Church’

Respondents referenced an apparent aversion in contemporary UK culture to engaging freshly with religious things. Several respondents identified society’s perception that the UK church holds outdated views around certain contentious issues, notably on human sexuality and partnerships.

A micro-church leader described how:

“there’s baggage linked in with the word church. I think it’s a loaded term: just the thought of what church means for people who’ve had a bad experience when they were younger, or faded out from the faith context, I think it’s quite loaded to ask someone, ‘do you want to come to church?’ And I’ve noticed that when I invite students, when the conversations kind of opened up and they want to explore faith, inviting them for a coffee or a walk, they kind of almost always say yes to that”.

2. Internal Factors

a) Leaders Feeling Over-Burdened

The most common structural hindrance was that “too much rests on the clergy. Respondents described themselves or their teams being too thinly spread with too much laid on a small number of people taking responsibility. Several leaders described how their predecessors had designed church practices which hindered innovation or personal missional discipleship. Others described the burden of expectations upon them to provide pastoral care, especially to elderly congregations, as detracting from their church’s missional focus.

b) Sense of lack

In contrast to best-practice leaders of inherited and micro-church models, it was notable that numbers of survey respondents described various forms of lack or scarcity as being hindrances to creating a culture of missional movement through the local church: such as finance, buildings being unfit for purpose, or small congregations. Some identified conflict or resistance within the local church or its wider denomination, such as resistance to change and development of missional church practices due to mindsets. “We are fighting to overcome a longstanding history of no outreach activity during a 40 year previous pastorate. I am struggling to change the mindset of most of the older congregation members but hopeful of better response from the under 65s”.

c) People’s Capacity

Old age was the most commonly identified area of capacity, affecting a congregation’s ability to engage with missional activities or new initiatives. Another was those churches working with people from experiences of socio-economic deprivation or addictions, who found mainstream resources difficult to engage with, or struggled with rhythms of life.

“We have found that the vast majority of training resources and discipleship tools are written/produced by middle class educated people and are so far removed from our context that people find it difficult to connect with them and access them. This is a huge challenge to us in our multi-cultural, inner city, urban context”.

3. Church Cultural Practices

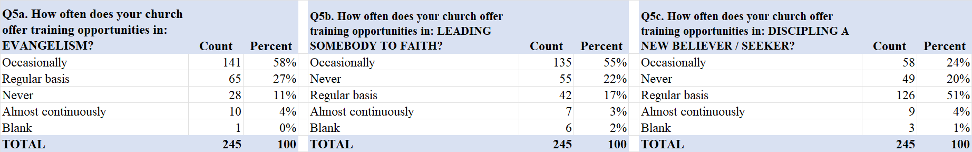

Many leaders in both research instruments identified a long-term cultural issue within British Christianity: that there had been insufficient modelling and training in personal missional discipleship within the average congregation. Findings show that the majority of churches offered a very low frequency of training in this field, for example in staple missional practices such as evangelism, leading others to faith and discipling a new believer.

Summarized by one respondent as,

“the fact that many people have never actually experienced being actively discipled themselves and therefore have no idea what it looks like if they were going to do it for someone else”

Several other leaders identified a traditional tie to the attractional model of church as a hindrance, for example:

“As a church we have been working intentionally to try and help our church engage with DMM principles. We have found this to be a challenge as people are conditioned to build an attractional model of church and a consumer/knowledge-based faith rather than an obedience-focussed method of disciple making. We are trying to adopt a hybrid system to maintain a passion for disciple-making and church planting whilst also continuing to gather as a larger church congregation”.

A further observation by some was that church programs were too full and demanding upon the time of congregants, which detracted from their ability to build relational networks outside of church circles with non-Christians.

4. People’s Preferences

Leaders identified a principal hindrance as Christian’s lives not being structured around missional discipleship, by choice, preference or distraction. Personal hindrances included a feeling of fear or a lack of confidence in sharing the gospel and a lack of significant relationships or social networks with non-Christians. The two most common hindrances were identified as people’s busyness, and a culture of individualism coupled with consumerism.

Consumerism was described interviewees in various terms, such as a refusal to commit to the costly lifestyle implications of discipleship and a fear to step out of people’s comfort zone. Several described a consumerist approach to church as the view that ‘I want it my way’ without enough of a willingness to lay down their lives of Jesus’ sake. One leader gave the example of challenging a congregant who said they needed deeper teaching:

“I said, ‘we need good teaching, but we also need obedient learners’. And they didn’t like that. One of the things that we keep on coming up against is that people like to have their brains tickled with theological insight. But when you actually say, ‘could you come and come with me and we’ll share the gospel on the streets this week?’, then they don’t want to be there”.

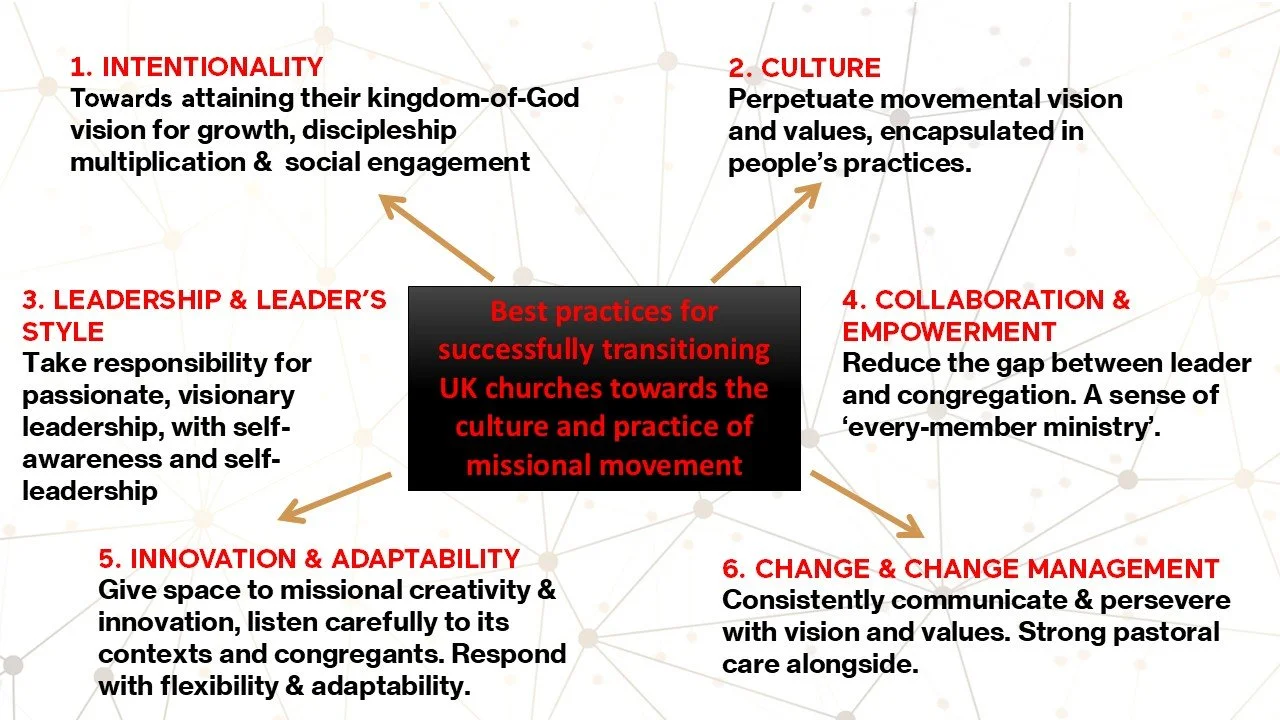

Best practices for successfully transitioning UK churches towards the culture and practice of missional movement

1. Intentionality

Best-practice churches in this study intentionally structured their church functions, ministries, groups/meetings, outreach activities and culture around attaining their kingdom-of-God vision for growth, discipleship multiplication and social engagement. Churches operated on a variety of ecclesiological and missiological models which enabled significant proportional growth in converts, but what was clear was that their leadership had weighed and chosen to pursue a particular goal, often over a process of years, and were willing to restructure the whole activity of their church community to achieve it.

Interviewees described processes whereby churches had corporately listened to God’s prompting over time and had been willing to critically review their present set-up and to pay the price of changing certain principles and practices to become more missional in their outcomes. Leaders described the process of managing that change and promoting a culture of responsiveness to context and culture, and adaptability in methodology.

It was evident that leaders applied great perseverance in keeping the vision and values central whilst instigating change and navigating resistance. One micro-church leader commented:

“The things that you sow-in now you will see in multiple generations time. How do we give those future generations the best ability to be able to continue to disciple themselves and make other disciples?”.

2. Culture

Best practice leaders worked to create a culture which perpetuated their movemental vision and values and was encapsulated in people’s practices. Two key areas which helped transition churches towards a missional movement:

a) Communication and Embodiment of a Church’s Vision and Values

The clear communication of vision and expectations for discipleship within churches was integral to achieving broad ownership from amongst the congregants. This was a key message from every best-practice interviewee. Several leaders spoke of “vision, values, vehicles and vocabulary” as helpful aphorisms. Generally, the vision and direction of travel were not open for debate, but the pace of travel and change and the vehicles to get there were more flexible. One leader captured the sentiment: “people seem to relate to leading with clarity, simplicity, courage and passion”. Micro-church leaders emphasized the adage of vision being “simple, repeatable, sharable”.

Key priorities of the church were discussed on a regular basis, with perseverance to the extent, as one leader put it, of being “boringly repetitive”. Vision was shared intentionally in its most concentrated form with key lay-leaders within the churches, including through vehicles such as huddles or focused training times.

b) The centrality of prayer and the place of faith

Prayer was described as fundamental and central for every best practice church, of all spiritualities and types. In combination with a sense of faith and expectation that God can and will move by His Spirit, it engendered confidence and missional action within congregations.

Experienced church leaders described the importance of striking a balance between maintaining a sufficiently pastoral culture so that people feel known, loved and invested in, and an outward-focused culture which galvanized people towards serving and reaching the lost. As one described their approach as

“keep it hot, keep it burning. But also having enough inward stuff to get that fire burning. I think the alternative thing is that you have a church that is so outward looking that a sense of growing spiritually, and growing in the word, growing in maturity: that isn’t there”.

3. Leadership and leader's style

A wide variety of churches were represented within both research instruments, from covenantal micro-church communities to large-scale attractional bodies with over 1000 congregants, yet in all examples of best practice the function of leadership was key. Leaders took responsibility for shaping their church culture in response to the guidance of God which was corporately discerned. They did so by applying their personal skills, by setting a personal example in their actions, and by creating a collaborative environment of empowerment.

“I think it’s got to start with passionate, visionary leadership. To be honest, if you are not just naturally embodying this as a leader, then it won’t flow out of you and people won’t catch it”.

When discussing their leadership styles, the vast majority of best-practice interviewees (leading churches of various shapes/sizes experiencing missional momentum) embodied a pioneering and apostolic leadership style. There were very few, if any, ‘pastors’ as per Ephesians 4.11–13.

Best practice leaders displayed significant levels of self-awareness and self-leadership. They described being less about people-pleasing but instead drawing their sense of identity from how God saw them. Leaders gave repeated examples of diligent and determined action to build towards an intentional culture of missional discipleship. They took responsibility to embody the vision and values, and to model obedience-based discipleship in a way that empowered others, including in concerted prayer and fasting. They displayed humility and authenticity in publicly sharing the bumps or failures in their discipleship journey.

4. Collaboration and Empowerment

Best practice leaders sought to adopt a leadership style which reduced the gap between ‘leader’ and congregation, of whatever size, by being as open and accessible as possible to people, and by modelling their vision and values. Their churches were heavily collaborative environments, focused on empowering individuals to take responsibility for their discipleship, with a sense of ‘every-member ministry’.

Collaborative leadership would seem to be key to avoid the pressure of expectations laid upon local church leaders, sometimes bordering upon personal burn-out, described as a significant hindrance to missional movement.

Interviewees reported how collaboration and empowerment meant that their teams had a great sense of ownership of decisions and their implications, so that the church’s ‘DNA’ was more easily and rapidly shared onwards. This commonly included the value of hearing God together.

“If our motivation for doing what we’re doing is only sustained by the degree to which I can communicate vision, then the moment it gets beyond me, we’re scuppered. So our vision and our conviction has to come from scripture, from God himself. I keep bringing the team back to God’s promises, His story”.

They described how team working enabled them to work better to their strengths. Around one-third of interviewees intentionally operated to an ‘APEST’ model whereby they appointed team members to cover each of the ‘five-fold’ ministries of Ephesians 4.11–13

Best practice clergy and leaders viewed themselves as missional coaches, looking to lead in a way which encouraged others to flourish and to avoid a culture of dependency upon senior clergy/leaders. As well as setting a framework and expectations for personal discipleship, they sought to hear people’s passions and ideas, and to champion others to run with them. “One of our leadership styles is definitely macro-managing rather than micro-managing. And if someone has an idea, we champion it and say, ‘yeah, go for it. We’ll give you everything we can do to support you’”. In this way, best practice leaders created environments which embraced and released creativity in mission and ministry. They sought-out spiritual leaders and missional pioneers, rather than functional administrators to set the tone for corporate church activities. One interviewee summed up this collaborative approach from central church leadership as “it’s not us for you, it’s us with you”.

They invested significantly in raising new leaders to generate the replication of the vision and values. Alongside training courses, this frequently took the form of one-to-one or small group mentoring based on opportunities for imitation, including in apprenticeship models for leaders such as internships or curacies. They consistently trained the body of the church in the fundamentals of missional movement, including evangelism, leading people to faith and discipling new believers. Larger churches heralded resources such as ‘discipleship pathways’ which map out a process and/or they offered training in revealing people’s personal calling and giftings, aimed at empowering a lifestyle of whole-life discipleship. However, the micro-church and DMM practitioners were the most intentional about linking personal discipleship to the raising of new disciples in everyday contexts. This was the focus of all almost their actions. They sought to instil movemental practices based on rapid obedience-based discipleship, typically through the three-thirds model, with the purpose of seeding this self-replicating behaviour into new generations of believers.

5. Innovation and Adaptability

Best practice churches exhibited a culture which gave space to missional creativity and innovation, and which listened carefully to its contexts and congregants, and responded with flexibility and adaptability. Leaders engaged in practices which empowered their congregants and consequently viewed one of the leader’s key roles as facilitating and resourcing missional initiatives. They had a practice of identifying small numbers of pioneers and early-adopters and supporting them to fan-into-flame the potential projects.

The key point is that best practice churches made significant efforts to lean into the innovative ideas or creative expression of their congregants, and to take action in response. They exhibited adaptive leadership, as they listened to their missional context, and championed responsive solutions. This adaption was partly fostered by a cultural expectation to innovate and a ‘have-a-go’ attitude. Furthermore, a value upon the freedom to fail was especially key around missional initiatives and attempts to reach out to people’s relational networks evangelistically.

6. Change and Change Management

Change was a regular feature of best practice church cultures, as was good change management. Frequent change was a particular feature of micro-churches and church plants/recent start-ups (including revitalizations). Best practice churches demonstrated the significance of flexibility. This applied to the place of faith, prayer and prophetic guidance.

The careful management of change was a defining feature of best practice churches transitioning towards the culture and practice of missional movement. As previously reported, leaders consistently communicated their vision and values and persevered with them in the face of inevitable objections or seemingly negative consequences, such as reducing finances or numbers of congregants willing to stay part of things. They focused upon raising leaders into a missional and multiplication ‘DNA’ and empowered those people to grow in their giftings and obedience-based whole-life discipleship. They devoted specific training, resources and the attention of staff/leaders to help to achieve this. They recognized the importance of good pastoral care as a basis to achieving their vision and values. Leaders representing churches of all sizes acknowledged that strong pastoral care was not counterproductive, since it formed a foundation from which to build an apostolic hub and engage confidently in mission.

Church leaders spoke honestly about their commitment to respond sensitively to discomfort and disorientation within their congregations around change and the embrace of movemental practices, often acknowledging their own past errors in mis-managing people’s sensitivities. Their change management techniques were not unique to a missional movement; they could apply to most group leadership. In times of significant change or discomfort, they had learned to amend the pace of change for a while and focus upon maintaining good relationships and connections inside the church. They sought to be honest, open and transparent about the likely impact of change. Many spoke of the importance of listening well, without changing the organization’s overall purpose or direction. It was key to paint a picture for people of where they belonged within the church and the contribution they could make, and to biblically anchor where the mission of the church fitted within the change proposed. “We try and make sure that everything we do publicly is as diverse and inclusive of some of those different groups as possible, so that people see people who are different to them and get to know them”.

Others spoke of being patient with ‘late adopters’ and giving good people time, being willing as a leader to travel with them, but not to release any significant responsibility to them at that point. Many described a willingness to let people leave their congregations with grace, if they could not adapt to the new realities. They acknowledged that it was important to address people’s disappointment and help them to deal with it, because otherwise it would lower the church’s passion for mission. One leader described himself adopting the posture of an “apostolic shepherd” when leading people through change.