Missional Movement Through the Local Church: Applying Movemental Principles in a British Context

by Rev Dr Nick Allan

Recommendations

Recommendations for the UK Church

The research project identified some significant deficiencies, at the level both of individual Christians and local churches in the UK, regarding the kind of conduct required to foster missional movement through the local church. It also offers some hope and encouragement for the future.

While Britain experiences a transitional phase in her history, as the vestiges of Christendom continue to fade and the task of re-evangelizing the nation looms larger, there is an opportunity to for churches to modify their principles and practices to be better suited to the evolving social and spiritual climate. In some respects, this task is already underway. Denominations and networks are prioritizing church planting with a vigour not seen since the nineteenth century. The question remains whether a focus upon planting mostly inherited-model churches will be sufficient for the task at hand?

This research has highlighted a lot of good practice amongst churches too. Yet, it reveals that it is possible to be a healthy missional local church without being a movemental one. While allowing for the many differences between the social and religious conditions of the UK compared to the Global South, there are still clear principles, practices and leadership examples to be drawn from rapidly multiply missional movements (like DMMs) which the majority of the UK church is not following. To implement the key elements which engender missional movements within churches (of whatever size and tradition) will require significant changes in their principles and practices.

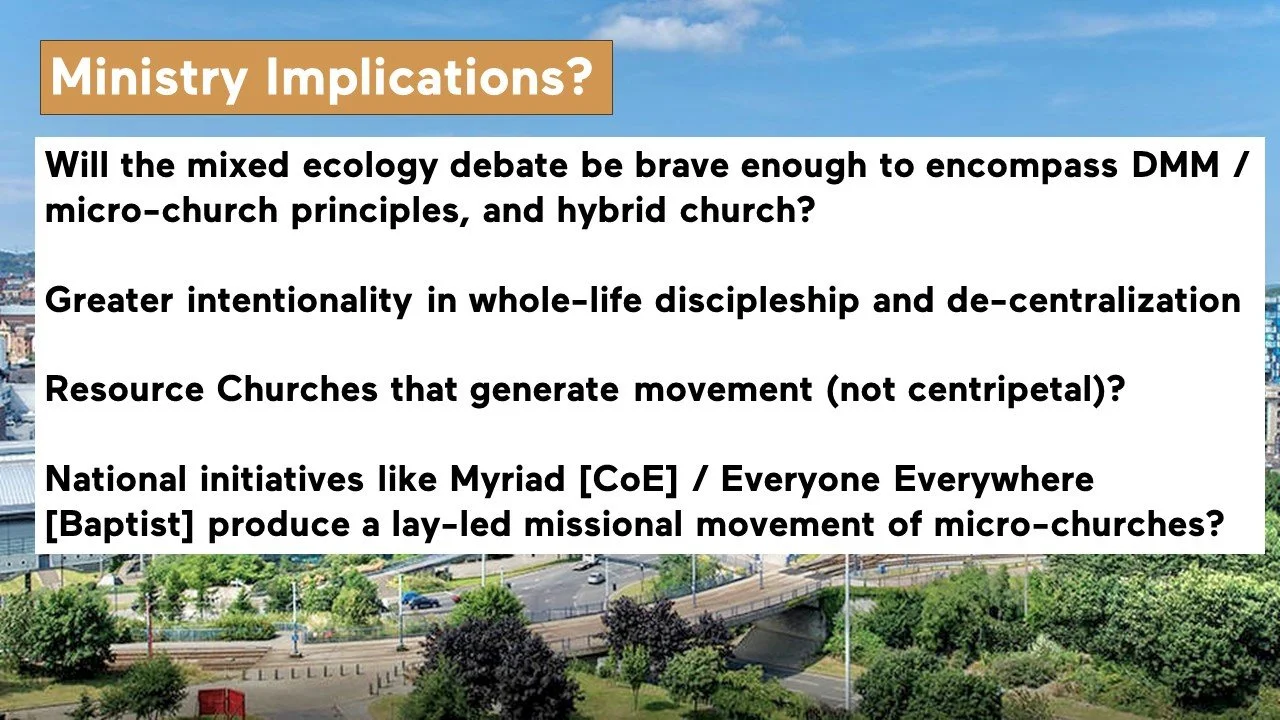

The reality in the UK is that the model of building-centred gathered church is long-established and unlikely to disappear this century. Therefore, my recommendations are pragmatic. The opportunity at hand is how best to transition a church beyond just serving a limited geographical and social focus, towards becoming an organically replicating discipleship movement, which also utilizes the best things about gathered church. The emergence of a hybrid model of church is the most likely outcome.

Alongside corporate practices, people’s personal practices must be modified too. The creation of a culture of courageous missionary discipleship must become the aim. That will require a paradigmatic approach, not merely a programmatic one. Local churches must foster the kind of attitude within their people and set the kind of example by their practices, which cultivate this kind of approach to living the Christian faith. The formation of disciples must merge with the task of evangelism. For some Christians, this will require a radical mindset shift. As Pope Francis writes, “Every Christian is a missionary to the extent that he or she has encountered the love of God in Christ Jesus: we no longer say that we are ‘disciples’ and ‘missionaries’, but rather that we are always ‘missionary disciples’”.

This will require a willingness to pay the price, both personally and structurally, to transition the average UK local church. At times it will require the break-up of inherited patterns of gathering and the interruption of comfortable individualism for the sake of multiplying the gospel. To act consistently for the sake of generating organic movement will require the gathered body of the church to be “broken” for the sake of the world.

There seem to be three areas in which significant shifts must occur to build the hybrid missional church of the future:

Perceptions

Leaders of inherited-model churches frequently articulated a sense of lack in people’s mindsets, in practices, in available resources, or in their cultural context being receptive to the gospel. They spoke of low confidence within their congregants relating to evangelism and in discipling new believers, allied to a sense of being intimidated by contemporary culture, and/or feeling ill-equipped to engage it with the gospel. Micro-church and DMM practitioners however, including those interviewed in this research, tend to be more optimistic despite being very small in number and influence in the UK. Their approach was to take personal responsibility for being obedient to the gospel imperative to be a disciple who raises new disciples in a simple, replicable fashion. They view their own lives as the plentiful resource necessary for the harvest (Matt. 9.37). Abundance is a key theological value which influences this mindset, and the UK church must embrace it.

Brian Sanders has introduced the micro-church philosophy to the southern United States and comments, “if we plant churches based on buildings (scarcity), money (scarcity), professional clergy (scarcity), or complicated work (scarcity), where is the abundance?” (Underground Church 179). The Bible outlines the movement of God and its capacity and expectation for reproduction which is for the blessing of all people and creation itself. Jesus inaugurated the organic, fruitful kingdom of God. He promised He would always be with His people (Matt. 28.20) by His Spirit (John 16.13–15) in their missionary task to build a multiplying church.

Principles

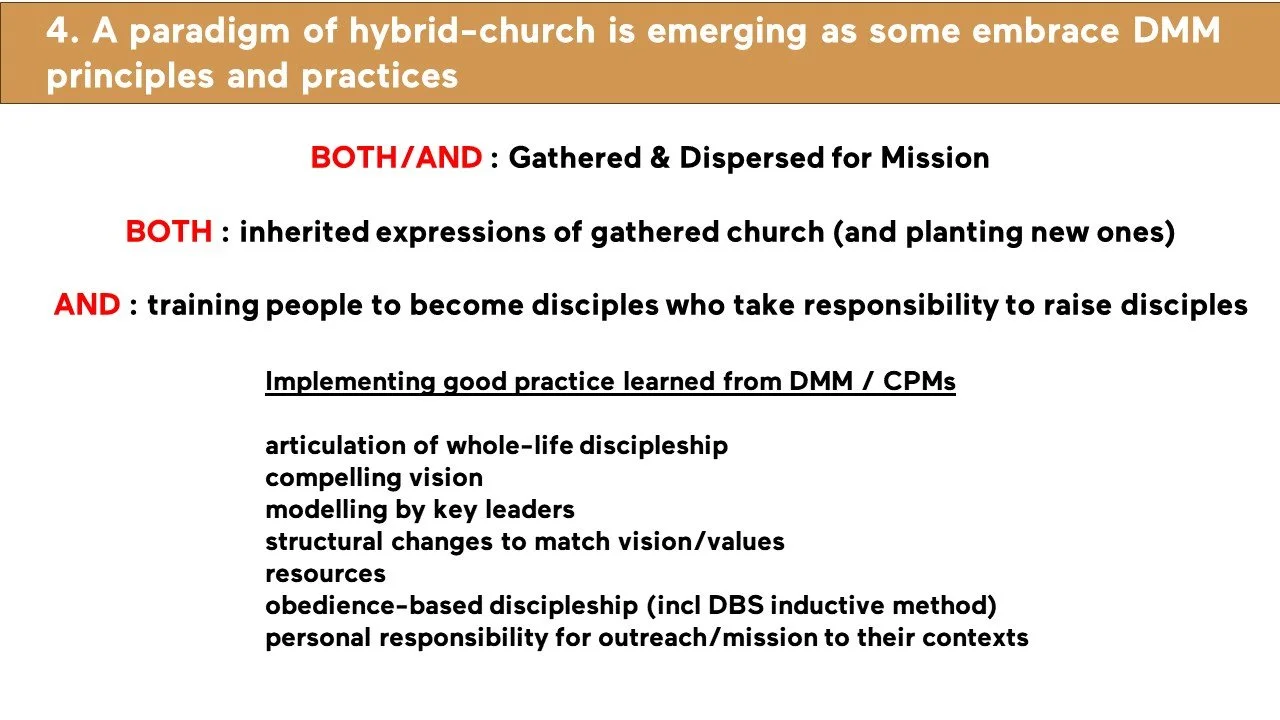

The principle of whole-life discipleship must become central to church culture. Christians must be encouraged and equipped to take personal responsibility to be disciples who also raise disciples. The strongholds in UK national culture and church culture, of busyness, individualism and consumerism, must be addressed head-on. This research repeatedly highlighted them as having the effect of eroding commitment, in mindset and action, to lifestyles of missional discipleship. At present a significant proportion of evangelical churches hold to the principle that the goal of discipleship is much more about maturing in personal faith than in publicly sharing faith or leading others to faith. This must be reversed, so that whole-life discipleship is seen as the goal of faith.

Practices

The task of the church’s leaders is “to equip His people for works of service, so that the body of Christ may be built up” (Eph. 4.12). Training and equipping in personal missional discipleship must radically improve within churches, away from its current tendency to focus upon issues of personal/spiritual maturity without being sufficiently intentional in tackling people’s perceived lack of confidence in evangelism and discipling others. This contrasts to the apprenticeship model employed by DMMs whereby individuals are taught from the start to take responsibility for the early-discipleship of new converts through Discovery Bible Studies and other tools. UK Christians must break their addiction to Christian content over Christian obedience. Greater personal accountability must be introduced, alongside greater intentionality. Some churches and diocese have now introduced ‘discipleship pathways’ or ‘Personal Discipleship Plan’ resources to aid this.

The most effective form of training in this regard is its modelling by Christian leaders so that many other people can see and imitate their example. The most effective missional churches are already led this way. To help people to learn how to take personal responsibility for outreach and discipleship follow-up, churches will need to reduce how many programmes and ministries they provide or facilitate centrally. Essentially, churches need to stop putting on so many evangelistic/outreach events for existing Christians to join in with, in favour of empowering Christians into lifestyles which integrate outreach.

The biggest shift needs to be the decentralization of the locus of power and authority within the local church. At present, churches are too clergy/leadership centric in terms of their financial structure and costs, where events and initiatives originate, how missional decisions are taken, and who implements them. Movements are by their nature decentralized. The early church valued apostolic leadership at a regional level, but it championed personal witness and discipleship, and local lay-led leaders to plant new Christian communities. The hybrid model of church will need to make space for micro-churches to form which are encouraged upon an autonomous trajectory from the start.

Common practices have been identified to help transition local churches towards missional movement

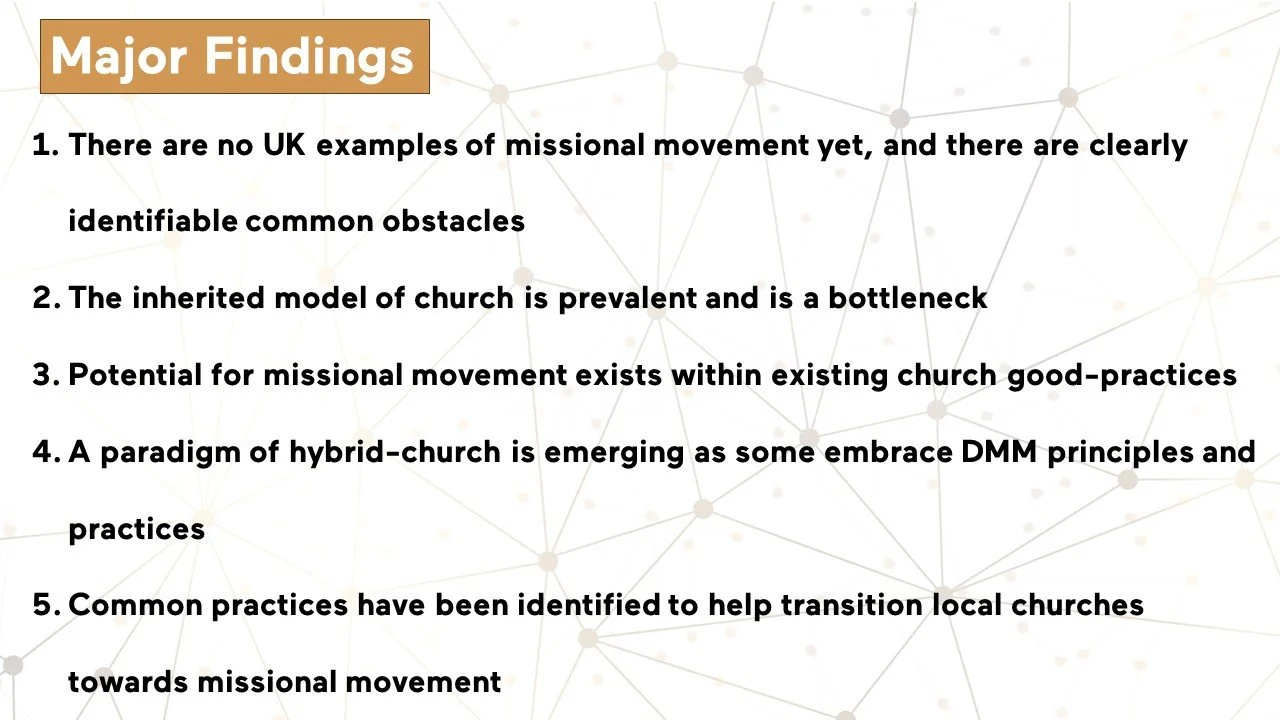

The UK in 2024 does not have any clear examples of viral missional movements. Yet it is feasible from this research project to propose several common practices to help transition local churches towards missional movement. The evidence for this finding integrates observations of good practice from a variety of churches which are highly missional and experiencing growth, from my literature review which proposes movemental theology, ecclesiology and missiology and has identified common practices of missional movements in the Global South, and an analysis of where similar practices are presently lacking in UK church practice. Proposals sit within four categories:

-

The choice of ecclesiology and model

-

Avoiding common obstacles

-

The power of vision and intentionality

-

Good change management

There is no one-size-fits-all model for missional church, and this research has observed that churches of various ecclesiological models can flourish in discipleship and mission. The missional church conversation is gaining traction. This is a transitional juncture in the British church. Her human, financial and physical capital is growing scarcer, but as a result the historic denominations are being roused to respond to the urgency of widespread lay-empowerment and church planting to further the missio Dei and the call of the Great Commission (Matt. 28.18–20). In doing so, they are catching-up with the British New Church Movement and immigrant diaspora churches who have acted on this basis for some decades (Brierley Consultancy, UK Church Statistics 1).

Missional church is not a prescribed set up things to do or a packaged vision for what church should look like, but rather a particular perspective on the church’s theological identity… it beckons us deeper into our theological imaginations for God’s presence and movement in the world. It raises the bar for discipleship and spiritual formation within intentionally cultivated Christian communities. It reorients church leadership toward guiding disciples into participation in mission. It expands and diversifies patterns of church organisation for the sake of mission. It informs the expectant planting of new churches through the creativity of the Spirit. It suggests deeper and more experiential approaches to church renewal. (Van Gelder and Zscheile 165)

This project found no evidence that there is one model of church which is more successful at producing missional movement in the UK at present. The inherited-model is certainly dominant for historic reasons, and micro-church models are slowly growing in traction. Some churches which are experiencing significant missional growth have gradually integrated the practices of both approaches to form a hybrid model of both/and. DMM theory proposes that obedience-based discipleship is rightly achieved in small-scale decentralized simple systems of church, while the evidence of this project shows that complex inherited-models can achieve significant conversion growth. However, their principal obstacle towards engendering movemental dynamics is their insistence on centralization. To further transition churches would therefore seem to require a both/and ecclesial model which achieves significant decentralization of power, authority and autonomy in missional discipleship and the forming of new ecclesial communities.

I propose from the evidence that healthy local churches should continue to invest in their gathered expressions which build “white-hot faith.” In addition, they should move away from the traditional small group/missional community model to focus upon their congregants forming semi-autonomous micro-churches which, in time, may exhibit all the marks of church. These micro-churches should be lay-led and contextualize their practices to enable devotion (“up”), to build a strong sense of community (“in”), and to share the gospel appropriately for their contemporary culture (“out”). Micro-churches based around homes and relational networks have the capacity to reach and raise new courageous missionary disciples through imitation and apprenticeship, so that they become rapidly multiplying. When not self-generated, their practical needs and oversight can be served through their close connection to the founding church.

The second step of transitioning a local church towards missional movement would be to avoid the previously detailed common obstacles which this research, and other scholars, has identified. Trousdale puts forward five categories of “spiritual malpractice” within western Christianity which inhibit growth:

· The reduction of the gospel of the kingdom and obedience to Christ to metaphors, not practice.

· A lack of concerted prayer from leaders and churches.

· The inappropriate role of clergy, being too specialized and too detached from everyday disciple-making, alongside a lack of lay empowerment.

· The tendency to choose knowledge over obedience as the essence of discipleship.

· Church institutions that do not sufficiently enable multiplication. (39–143)

During my interviews with leaders of good-practice churches, it was obvious that they spent a lot of effort trying to avoid each of these pitfalls in various ways.

The third step of transition is to envision and engage the whole body of the local church towards a holistic lifestyle of missional discipleship. “Volunteering alone won’t ever get us to gospel saturation, only calling will” (Ford et al. 176). Leaders must introduce and persevere with—through communication, modelling and complimentary structural changes—a vision for missionary discipleship beyond the church walls, helping people to embrace the costs and take personal responsibility for whole-life-discipleship in the power and joy of the Spirit. Good-practice leaders exhibited strong leadership and excellent communication of a church’s vision and values. They were relentlessly intentional in key areas (discussed above) and structured the church’s meeting and working practices to match their vision and values, frequently being willing to disrupt existing modus operandi if necessary. They sustained this intentionality over a period of time, which brought genuine cultural change. The single most significant element which I identified is when leaders were personally willing to model missional discipleship. They passionately carried the vision for this, they practiced it consistently and they shared stories of their own, and others’, attempts to live missionally: all of which empowered their congregants to do likewise.

The fourth step to successful transition is strong change management. Church leaders invested heavily in change management to transition their cultures towards their desired vision and values.

“The church as a pilgrim people is called to indwell those spaces of intersection and change, meeting people amid the flux of dislocation and identity seeking that is the norm for a globalized, postmodern world. This calling invites the church out of closed, settled forms of community life into flexible, adaptive, relational encounters. ”

In many respects the research findings in this area were so universal that they could have applied in most fields of managing people. Nevertheless, adaptive leadership is a key facet of contemporary church ministry. Church, says Bolsinger, must be willing both to acknowledge the scale of the problems/challenge ahead in today’s unchartered waters, and to see them as an opportunity to adapt and towards adventure. “In the Christendom world, speaking was leading. In a post-Christendom world, leading is multi-dimensional: apostolic, relational and adaptive” (Bolsinger 37). As a body they must go together into the call they have received, with an openness to new methods, to learning, to adaptation, to transformation, and even to the potential of loss and pain in the undertaking. Good-practice leaders described themselves as mission-coaches and mission-enablers, and they invested heavily in training lay-people and in addressing obstacles/objections while remaining true to their vision and values. The corrective I add from observations in this research of such strong leadership cultures remains my primary point. In order to transition towards missional movement, strong healthy local churches must decentralize power and autonomy in mission more intentionally away from their current orbit around visionary-leaders, consumerist gatherings and any definitions of discipleship practices that do not involve reaching and discipling the lost.

The national picture

There remains a question-mark about whether our national Church will be brave enough to encompass DMM/micro-church principles within its mixed ecology. The implications of encouraging lay-led micro-churches are very significant for all centralized church networks. The national church bodies should encourage DMM and micro-church far more. They should elevate their voices and make efforts for the majority church to learn from their experience. For if the Church is to truly missional, it must allow for significant diversity in expression, and be willing for the ‘trellis’ of its organization and finances to serve the ‘vine’ or organic growth and varied expression.