Missional Movement Through the Local Church: Applying Movemental Principles in a British Context

by Rev Dr Nick Allan

Theology

This is a vastly abridged version of the doctoral thesis Ch 2 literature review, available in full here.

Shorter version first, then a longer version follows below.

SHORT VERSION

This project investigated the literature around the topic of whether in the UK today a typical healthy local church in the inherited model might transition to becoming a missionary movement of people that impacts its whole locality by generating rapidly reproducing disciples who make disciples.

One of the foundational biblical narratives is that of the missio Dei. It illustrates the nature of God the Trinity and indicates what the nature and action of God’s people, who bear His image and share the calling to be “a blessing to all nations,” ought to be. It is a missional calling, set in place through creation and the establishment of God’s covenants and it finds its fulfilment in Christ and His body the church. All of this undergirds the motif of the movement of God: motus Dei. The relationality of the Trinity overflows in God’s interaction with His creation. Movement is an organic reality represented in creation itself, and it is a reflection of the outreaching nature of God. It is reflected in the nature of the People of God who are endowed with the calling and capacity to reproduce, for the sake of the world. It is embodied in the person and work of Jesus Christ who began a discipleship-reproduction movement that has been growing ever since. The church of Christ began as an evangelistic and church planting people movement as depicted in the book of Acts, which some scholars treat as paradigmatic, depending upon their hermeneutic. The history of the early church suggests that despite its grassroots basis and lack of influential power, widespread evangelism lay at the core of its transmission through society so that it spread in a movemental fashion.

According to the literature, the institutionalization of the church in the West seems to suggest that when movemental principles are neglected, the reproduction of the discipleship ‘DNA’ of Jesus also declines. In the UK, it took the dissenting church movements of the reformation to begin a recovery. Most notably for the UK was the Methodist revival of the eighteenth and nineteenth century, at the core of which were easily reproducible movemental principles and practices. These led to widespread transformations of society through a combination of Spirit-filled evangelism and social good works. Modern missiologists argue that for the post-Christendom UK church to be truly missional and responsive to its local contexts it must recover the full import of these trinitarian theological foundations, by exhibiting lives of incarnational mission and participating in the movement of God.

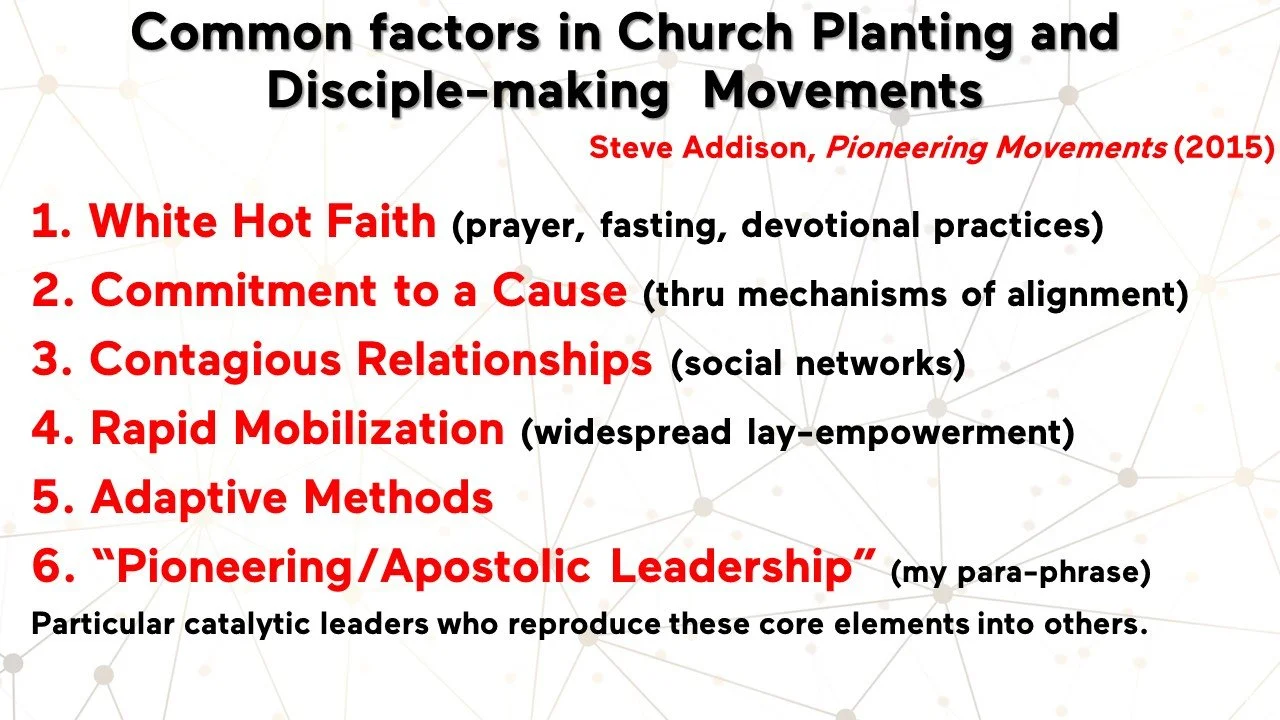

Church Planting Movements (CPMs) in the Global South are a modern-day phenomena, attracting increasing study and attention from missiologists since the turn of the century, as the evangelical church in the Global North struggles with overall decline. Of interest to this study are the principles and practices of Disciple Making Movements (DMMs). Addison (Movements; Pioneering) proposed six core elements of a Christian disciple-making movement: “White Hot Faith”, “Contagious Relationships”, “Commitment to the Cause”, “Rapid Mobilization”, “Adaptive Methods”, and a concept which can be termed “Pioneering/Apostolic Leadership”. These six factors formed the typology framework for the survey research of UK church leaders.

The question posed by this research project is whether, and how, the core elements of DMM may be transferable into the cultural, sociological and ecclesial conditions of the UK. The most significant sociological hindrances lie in British society’s widespread absence of natural networks of extended-family type close relational communities, since in the Global South these are one of the major factors which help the rapid reproduction of the gospel and discipleship. Other hindrances to movement within Western inherited modes of church are identified as: clergy-dominated systems rather than widespread lay empowerment and apprenticeship-based discipleship and leadership development; low levels of intentional evangelism and church planting; bifurcation of social action from supernatural evangelism; a culture of consumerism and low commitment within church life; and an addiction to consuming Christian content over rapid obedience to Christ.

Finally, contemporary missiologists propose that a way forward in the West could be to adopt a hybrid model whereby churches adopt the most significant practices of CPMs/DMMs but remain pragmatic that inherited modes of church are deeply embedded. The focus should be upon raising up leaders and laity into mission, from within the existing church. They propose decentralizing the locus of power and authority within the local church and empowering all believers to adopt missional practices and to creatively contextualize the gospel, so as to create momentum towards missional movement.

LONGER VERSION

Introduction

This section summarises the literature relevant to movemental principles and practices. It begins with a consideration of the biblical understanding of the movement of God and the missio Dei. In the Old Testament (OT) this is closely tied to the creation and exodus narratives, and to the concept of covenant blessing for the sake of Israel and, ultimately, for the benefit of all nations. The New Testament (NT) segment first illustrates a continuity and development of certain themes within the OT, then it considers the motif of organic multiplication in the gospels, followed by lengthy treatment of missional movement and discipleship-reproduction in the book of Acts.

The second section looks at theological foundations, emphasizing the implication of trinitarian relationality, the incarnation and human participation in the movement of God. It assesses a missiological response as the natural progression from the sending nature of God to the sent nature of the church. The ecclesiological response is outlined as the church engaging in its innate ‘missional-incarnational impulse’ in response to the nature of God, which is contextual theology in action (Hirsch, The Forgotten Ways 129). The section explores the challenge before the post-Christendom UK church to be truly missional—to understand and be responsive to its local contexts. It concludes with offering four steps towards a theology of movement.

The third section considers people movements from a sociological perspective and the movemental spread of Christianity in the early centuries of the church. Its focus is the contemporary phenomena of Church Planting Movements in the Global South, with a particular focus upon Disciple Making Movements (DMM). The principles and practices of DMM form the foundation of the primary research conducted for this project. Scholars’ assessment of the key factors behind the grow of DMMs is presented and critiqued from the perspective of how and whether they may be transferable into the cultural, sociological and ecclesial conditions of the UK.

BIBLICAL FOUNDATIONS

The movement of God: Motus Dei

Movement is one the key motifs in the biblical narrative. Its understanding begins with a treatment of missio Dei, the missional nature of God, which defines the purpose of the people of God through the ages. Running throughout the Old Testament (OT) narrative is an expectation, set by YHWH, of fruitfulness, reproduction, and the spread of the people of God for the benefit and blessing of the whole of creation. This is the movement motif, or in the Latin phrase recently proposed by Warrick Farrah, the motus Dei (Farah, “DMM and Mission”). It offers a biblical hermeneutic framework within which some scholars ground an understanding of the roots and motivation for the contemporary practice of evangelism and the formation of new Christian communities, including church planting.

Old Testament foundations

The movement motif sees God call a chosen people into covenant, fundamental to which is establishing the practice of the communal worship of YHWH in specific places and occasions. This is a forerunner of the apostolic function which emerged amongst the New Testament church of establishing multiple new covenant communities for the worship and proclamation of Jesus the Messiah as God.

The motif of movement and the mission of God flows throughout the OT. The People of God who become established in the Promised Land as the nation of Israel are not permitted to become static; they are swept into a continual narrative of movement at YHWH’s behest. The great Exodus does not merely save the Hebrews from slavery. It demonstrates the power of God to the surrounding national powers. The newly formed nation of Israel interacts with those nations which surround it, in battle or trade, always for the display of God’s splendour (Isa. 43.7, 61.3). During their period of exile, the Israelites continue to establish ways to worship YHWH regardless of their geographic location because their identity is so strong as the People of God. The return from exile, a major event in Jewish history, is also heralded by the prophets as ultimately being of benefit to all nations.

Throughout the OT narrative therefore, the establishment of God’s people is for the enjoyment of God’s creation blessing and his promise to “increase you a thousand times” (Deut. 1.10–11). All the while, they carry the mandate, unfulfilled in the OT histories, that the intent of their blessing is also that “all peoples on earth will be blessed through you” (Gen. 12.3).

The language of love, covenant and election does not necessarily relate or translate to a modern understanding of ‘mission’ (Stroope). The movemental biblical imagery is like breadcrumbs laid out on the people of God’s exponential trail towards comprehending the ever-extending missio Dei. Fruitfulness and blessing, God’s presence and promise being established for the sake of the whole world, do not find their fulfilment until the New Testament. “What we find rather is the clear promise that it is God’s intention to bring such blessing to the nations” (C. J. H. Wright The Mission of God 503).

New Testament Foundations

Some cautions

Within the body of scholarship there are considerably different hermeneutical perspectives to the place of mission in the NT. Authors tend to hold to a clear preference, which is obvious in the body of literature about the ‘missional church’ since the turn of the twentieth century. Both Derek Morphew and David Bosch in their magisterial treatments prefer to highlight the gospels’ focus upon Jesus inaugurating the Kingdom of God amongst the Jewish believers, while, in Bosch’s phrase, by his ministry He also opens the “road” of mission to the Gentiles, since “there are no simplistic or obvious moves from the NT to our contemporary missionary practice. The Bible does not function in such a direct way” (Transforming Mission 24). For missiologist Lesslie Newbigin, “the previousness of the kingdom” is what naturally and correctly must shape the church. “Mission is not something that the church does; it is something that is done by the Spirit, who is himself the witness, who changes both the world and the church, who always goes before the church in its missionary journey” (The Open Secret 56). Caution is required in interpreting the place of church planting in the New Testament. It is absent in the gospels but a key part of the narrative in Acts, and the pastoral epistles are written to fledgling church plants. The balance comes in appreciating that the movement of God through the coming of the kingdom of God are the predominant themes. As the gospel is shared and people experience discipleship and spiritual growth, so the church is formed, which can take many forms. Thus, for Murray church planting is an “option” in the NT, but not an “imperative”, and while we cannot argue for a “biblical rationale” for church planting, we can certainly find “biblical perspectives” (Murray, Church Planting 71–72). Notwithstanding, in assessing the theme of multiplication throughout the biblical narrative, there are significant continuities between both testaments. Christopher Wright says that “the New Testament picks up and brings to fruition all the theology and expectation of the Old Testament in relation to God and the nations” (The Mission of God 505). The foundations were laid in Jesus for a new movement to begin, which reframed the message of the kingdom of God and reframed the identity of Christ’s followers (echoing Exod. 19.5–6) as “a chosen people, a royal priesthood” (1 Pet. 2.9). They become known as the Church and carry the capacity for the reproduction of the kingdom of God to every people group and ‘ethnos’ (Matt. 28.19).

Organic Multiplication Theme in the New Testament

The organic theme, first introduced in the Genesis creation narratives, featured heavily in Jesus’ kingdom teachings. The command to creation itself, and God’s people within it, to be fruitful and multiply is foundational in God’s design for life. Jesus used a variety of organic, reproductive metaphors to describe the kingdom of God and the fruits within people’s lives of the kingdom coming. The New Testament seems to have understood church as a mixed ecology, unified around Christ yet diverse in its expression.

Hirsch contends that Jesus instils within every believer the coding and capacity for self-replication, what he calls “missional DNA” (76). Jesus commanded that every believer, born of conviction and prepared to suffer for the cause, should plant the seeds of the gospel into the hearts of unbelievers (Mark 4.14). Within the NT narrative there is a clear expectation that the organism of the church should engage naturally in “non-identical reproduction” (Lings 30). These are key building-blocks in the intended movemental nature of the local church.

Movement Motif in the Book of Acts

Luke’s account in the book of Acts continues the narrative of the impact of Jesus’ ministry and the formation of the church of Christ in the world. Hermeneutically, there is a range of scholarly opinion about how directly we may apply the principles and practices offered in the account of the movement of the early church to our contemporary context. For Acts to retain much relevance for today, many scholars and certainly most missiologists advocate for a qualified but confident missional hermeneutic when assessing the purpose of the texts. Luke-Acts is written upon the prophetic foundations of the OT and demonstrates the beginnings of fulfilment of the missio Dei through the event of Jesus and the birth of the early church.

There is an obvious structure to the narrative of Acts, which is structured around what Lings calls the three ‘ec-centric’ phases which mirror Jesus’ command of 1.8, whereby the gospel spreads from “Jerusalem” (ch. 1–7), to “Judea and Samaria” (ch. 8–9), and later to “the ends of the earth” (ch. 10–28). Acts and certain epistles outline the rapid spread of the gospel through the empowering presence of God through his Spirit, and the catalysing witness of key apostles. Following Jesus’ pattern we see the reproduction of disciples and the missional movement of God’s people, the church.

Behind such a move were a few key figures - Catalysing apostles who were instrumental in sowing the seeds of this new covenant movement. “There is a discernible thread of meaning running through the New Testament concept of “apostle.” That thread is the apostolic “work” of pioneer church planting” (Snodgrass 270–71), undertaken by an itinerant missionary team alongside Paul, which included Barnabas (Acts 14.3,14), Epaphroditus (Phil. 2.25), Titus (2 Cor. 8.23), Apollos (1 Cor. 4.6,9), Timothy (1 Thess. 2.6). These various apostles did not plant churches in their image. They saw themselves as partnering with God’s sovereign work by planting gospel seeds (1 Cor. 3.6–7) and by strategically forming relational networks of household/oikos, who regularly gathered as ekklēsia. Regional networks formed, overseen loosely by the apostles, such as in the region of Galatia (Gal. 1.2), Ephesus (Eph. 1.1), Corinth (1 Cor. 1.1–2), and the “exiles scattered throughout the provinces of Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia and Bithynia” (1 Pet. 1.1). These communities saw themselves as part of a bigger whole, the movement of the gospel forming the people of God. The New Testament church was a relational network, not simply a dispersal of local independent churches (Klinkenberg 213).

New churches form, in a succession of new localities with the purpose of multiplication, across the Mediterranean world, the result of which was the widespread propagation of the gospel. This occurs typically as multiple small ecclesial communities are planted, through the oikos networks and homes of new converts (1 Cor. 16:1; 2 Tim. 4:19).

There was a strategic element. Centres of evangelism, church planting and training are established in key cities in the Roman empire (Acts 13:49). Paul arguably adopted a regional saturation strategy which, in contemporary understanding, equates to both pioneer church planting by an individual catalytic influencer, and churches planting other churches. Craig Ott goes so far as to argues that “rapidly growing movements, which in some cases saturated whole regions with the gospel, were evident in the experience of early Christian mission as reported in Acts” (Ott 103). Similarly, Tim Keller believes that in Acts the multiplication of individual converts is as natural as the multiplication of churches. “When Paul began meeting with them they were called ‘disciples’ (Acts 1:22), but when he left them, they were known as ‘churches (see Acts 14:23)” (356).

THEOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS

Just as an understanding of movement from the biblical narrative begins in Genesis with the words and action of God, its theological foundations begin in the doctrine of the Trinity: the very nature of God. This doctrine explores the nature and interrelationship between the three persons of the Godhead, emphasizing both their unity and diversity. The persons of the Trinity are at once one, coequal and coeternal. They are inseparable yet distinct in their radical interconnectedness, sharing a “differentiated unity”, having distinguishable relationships unique roles in relation to creation and redemption (Seamands 112). Love is at the essence. The persons of God the Trinity engage in mutual relationships of love, communion, and self-giving (McGrath). Thus, “to participate in mission is to participate in the movement of God’s love toward people, since God is a fountain of sending love” (Bosch 289–90). Theologically, this grounds a consideration of movement in the implications of trinitarian relationality, the incarnation and human participation in the movement of God.

Missio Trinitatis

The concept of missio Trinitatis shapes the way Christians engage in mission. It invites believers to participate in the ongoing movement of God in and towards the world. It also highlights the inseparability of mission and the Church. The Church, empowered by the Holy Spirit, serves as the visible embodiment of God’s mission in the world. It allies closely to soteriology and eschatology to demonstrate that God’s people may participate in a movement towards a positive ending. It is the hopeful perspective of God calling people into a movement of salvation and towards the culmination of that movement.

Given the New Testament witness just described, it is still legitimate to describe the default posture of the church as being sent, called-out, on the move and in mission. In summary, the missio Trinitatis means that the church is always participating in the motus Dei, the movement of God. The church ought to view itself as at once gathered and dispersed, since participating in the Trinity is not a one-way relationship and God’s ‘sending’ is never unidirectional. The implication of trinitarian reciprocity is that God responds to the conditions of the world into which the Son was sent, and His church continues to be sent. The expression of God’s kingdom, and therefore the experience of mission, is a two-way affair. Perichoresis represents this profound interplay and reciprocity both within the triune God and their relationship to the world. Christians should expect to be changed by the very contexts into which they seek to plant seeds of the gospel.

Missiological

Missiologically, it follows that the churches which are formed in response are designed and intended to grow and multiply, as a reflection of, and participation in, the Trinity. The great commission calls for discipling of all ethnos, all distinct people-groups on the planet, which requires the movement of the gospel beyond its present boundaries. There is a movemental progression from the sending nature of God to the sent nature of the church, then and now.

Since the 1990s the North American, UK and Australian church has produced a large volume of work within the ‘missional church’ conversation, mostly by reflective practitioners, seeking to integrate Trinitarian doctrine with missiology and ecclesiology. These would include: Andrew Walls; Michael Moynagh; Mike Breen; Michael Frost; Alan Hirsch; Eddie Gibbs, Ed Stetzer, Neil Cole; Roland Allen (rediscovered a century after his publications); Tim Keller; and Stuart Murray.

Contemporary Christian multiplication movements

The theology and biblical witness outlined suggests that healthy growing churches ought to aim to grow not just through gentle addition, but the multiplication of disciples.

Since around 2000, interest has been growing from missiologists around the principals and practices of Church Planting Movements (CPMs) and Disciple Making Movements (DMM) which are apparently very successful at generating missionary movement in developing world contexts. There is steady body of research and reportage emerging, including a compare and contrast approach targeted to both inform and provoke the church in the west.

CPMs centre around establishing new Christian communities or churches in unreached or underserved areas. Their objective is to initiate and multiply self-sustaining local churches, typically small-group sized, that reproduce and expand, through intentional strategies such as raising local leaders, widespread evangelism and a reliance upon the work of the Holy Spirit (Farrah 2020) and the supernatural power of God.

It is not until such an enterprise has multiplied several times that observers are ready to denote them as movements. “We defined a Church-Planting Movement as “an indigenously led Gospel-planting and obedience-based discipleship process that resulted in a minimum of one hundred new locally initiated and led churches, four generations deep, within three years” (Watson and Watson 4). However, from those authors offering transferable principles into a Western context, there is, perhaps surprisingly, no expectation that multiplication will begin immediately or rapidly. They report that momentum tends to build quite slowly before it hits a tipping point to expand rapidly, sometimes referred to as ‘exponential growth’ or a ‘hockey stick growth’ pattern. For Watson, it is not the number of small churches planted, but the number of leaders raised which creates the tipping point. “When we focus on catalyzing Disciple-Making Movements, we define success by reproduction. We really don’t care how many churches you have planted…Success, for leadership, is defined by how many new leaders a leader reproduces every year” (Watson and Watson, Contagious Disciple-Making, 36). There are parallels with how scholars like Stark (The Rise of Christianity) and Kreider observe the ‘patient ferment’ by which the early church worshipped in secret or in local homes, yet by their lifestyle of evangelism and good works achieved the spread of Christianity across the Roman Empire over three hundred years.

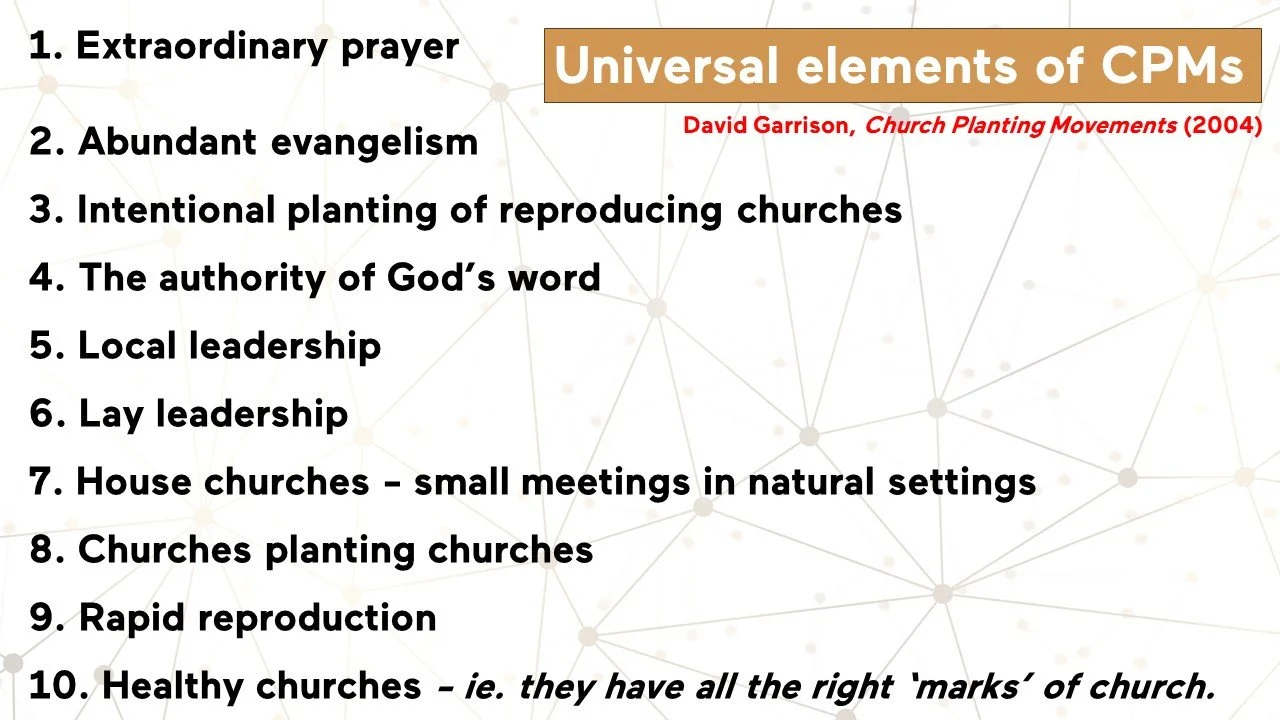

In 2004, David Garrison identified ten universal elements in every Church Planting Movement:

Disciple Making Movements (DMMs)

There is slightly a differentiated field within CPMs, that of Disciple Making Movements (DMMs). Their focus is narrower, placing a strong emphasis on making and multiplying disciples, rather than churches. The goal is to see individuals not only come to faith in Christ but also become committed followers and reproducing disciples who can make more disciples.

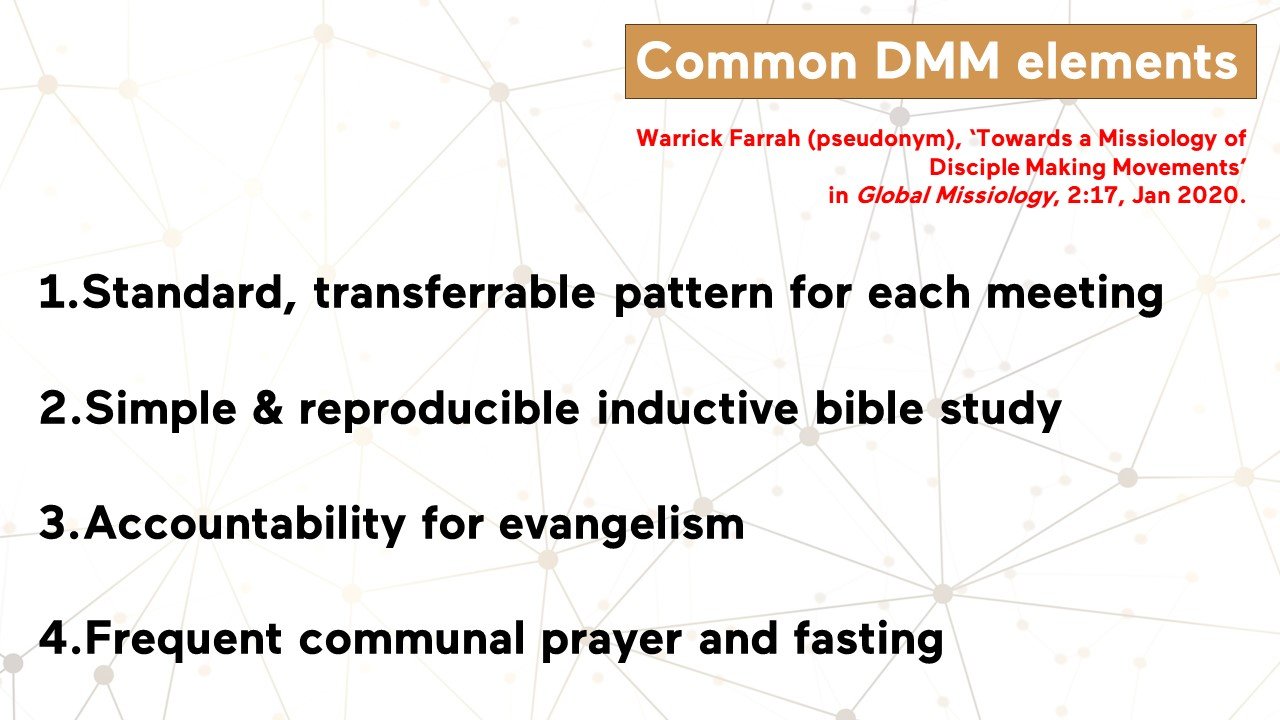

They use a simple, repeatable pattern when meeting, an inductive bible study method, they promote strong accountability for personal evangelism, and they champion frequent communal prayer and fasting

(Farah, “Towards a Missiology of Disciple Making Movements”).

It is difficult to quantify the numbers of people converted and active within DMMs. A 2019 estimate suggested around 73 million believers in over 4.3 million churches within 1035 documented movements (Long). And numbers keep growing.

Six marks of a Disciple-Making Movement: As a Typology for Research

Steve Addison proposes six common core elements of a Christian disciple-making movement. His six elements form the basis of the typology for this project’s primary research conducted into the contemporary practices of mission-minded churches in the UK, as outlined in the Research Section.

“Spiritual malpractice” in the western church

Having identified good practice, some writers have also identified what Gerry Trousdale calls ‘spiritual malpractice’ in Western Christianity which inhibits movemental growth from occurring (The Kingdom Unleashed, pp. 39–143)

1. the reduction of the gospel of the kingdom and obedience to Christ to metaphors, not practice

2. a lack of concerted prayer from leaders and churches

3. the inappropriate role of clergy, being too specialized and too detached from everyday disciple-making, alongside a lack of lay empowerment

4. the tendency to choose knowledge over obedience as the essence of discipleship

5. church institutions that do not sufficiently enable multiplication

Trousdale offers several observations of what the church in the Global North ought to do differently:

· Models of ministry based on what Jesus did

· Abundant Prayer

· Equipping ordinary people in power of Spirit, through apprenticeship and reproducibility

· Life in the Holy Spirit

· Develop collaboration and strategic partnerships to help spur movement

· Do not rely on your own resources, including finance and buildings – they must come from God

· Focus on kingdom ministry: compassion and healing, which will naturally initiate spiritual conversations

· Courageous leadership, sacrifice and persecution

· Kingdom Paradigms that can multiply – compared to current static and expensive models

There is some critical analysis of DMM theory. A number of missiologists claim that the figures are probably overestimated. Others critique the early portrayals of CPMs and DMMs for an over-emphasis on their rates of growth at the expense of other factors which build spiritual maturity. The most significant critique of the methodology lies in a key factor that seems to make it so successful in the Global South, which simply does not translate into Western urbanized contexts: the sociological factor of pre-existing relational networks into which the gospel may easily ‘seed’, extended family households, often called the oikos. These are largely absent from contemporary British society outside of settled working-class estates, or recent immigrant populations.

We must acknowledge that the sociological conditions of the global south are quite different from our European, post-Christendom context. We should avoid a simplistic ‘cut & paste’ approach of assuming that replicating the key attributes of DMMs will inevitably bring about missional movements in the UK

Bob Hopkins argues that three factors are necessary for a movement of God:

1. the intrinsic power of the gospel when it is proclaimed;

2. the mystery of the Holy Spirit moving at particular times across history (such as the Weslyan revival/renewal)

3. a host culture which has pre-existing social structures that act as conduits to transfer the gospel rapidly through homogenous households (the equivalent of the New Testament ‘oikos’), or close affinity groups and social networks (Hopkins, Personal Interview).

In the Global North we must “let go of the unrealisable mirage of multiplication movements in our Western fields” but we should learn from our mistakes and persevere with DMMs other fruitful factors, “to the long haul of costly unspectacular counter-cultural disciple-making mission” (Hopkins, Miraculous).

Commonly hindrances to movemental practices in Western / UK churches

I addition to Hopkins’ crucial observation about the missing sociological factor of ‘oikos’ there are several other commonly, although rather anecdotally, identified hindrances to movement in Western, and by extension, British church culture.

· The widespread institutionalization of church is criticized by many, including the observation that available money can tend to determine strategic goals, and lower their expectations as a result.

· Institutionalization is allied to a lack of lay empowerment and an over-emphasis and controlling over-centralization of the clergy, detaching them from the everyday function of disciple-making. This means that new believers are not typically raised rapidly into leadership in their indigenous contexts.

· Christian Selvaratnam illustrates how discipleship models (if they exist) are rarely based on an apprenticeship method, and so the leadership pipeline is slow or non-existent in most local churches. As a result, there are typically low levels of intentional evangelism, and discipleship is segmented from a vision for church planting or the multiplication of various forms of church suitable for the unreached (Selvaratnam, The Craft of Church Planting).

· Similarly, this seemingly lower level of confidence in the power of the gospel tends to produce bifurcation in the average UK church, which is the separation of social good/action from supernatural demonstrations of the kingdom of God.

· A final category may be described as atrophy. While CPMs exhibit “white hot faith” and an obvious “commitment to a cause” (Addison, Movements), the Western church has been criticized over the past two decades for a seemingly steady decline in confident its engagement in public discourse, and a deterioration in its general ‘health’ and discipleship capabilities.

Applying the lessons of movements to the Western evangelical church

Some contemporary missiologists offer the positive attributes of historic and contemporary movements as a framework for a renewal of the Western evangelical church in the twenty-first century. This forms the basis of the primary research within this research project, in the hopes of locating good practice for European churches who seek to reverse the decline of mainstream denominations.

Bevins believes that the Western church requires a movement of renewal before it may recover the dynamism of the early church or replicate the multiplication of the Global South (Marks of a Movement). Farah and Hirsch collaborated to offer a new ecclesiological framework for the practice of the Western church, in order to better integrate the apparent benefits of DMM and social movement theory, which would bring about “a paradigm shift in church mindset” (Farah and Hirsch). They contrast typical Christendom-influenced ecclesiology against movemental ecclesiology, as follows:

Figure 2.1: A Paradigm Shift in Church Mindset (Farah and Hirsch)

American church leaders Wegner and Ford adapted Brafman and Beckstrom’s 2008 foundational concept of the “Starfish and the Spider” and overlaid it upon a compendium of Alan Hirsch’s works, through the lens of their applied experience. Their attempts to introduce The Forgotten Ways six elements of movement, which he calls “mDNA”, into their churches are assessed and new insights offered (Ford et al.). One central argument of the work is how the form of church matters less than the form of power dynamics at work within a church, that is, where the momentum for mission or action originates from.

Lim calls for the relocation of ecclesiology and ecclesial practice away from Christendom assumptions which tend to mean that “church” is seen as building-based and clergy-centric. From the missio Dei basis that Christ the Son and the church are sent into the world, he rejects the church’s historic vision of “Christianization” in favour of the infiltration and subversion of existing cultures with the culture of the kingdom of God (Lim). He offers three categories: “Holy People” locate the priestly function away from the clergy and into the priesthood of all believers (1 Pet. 2.5–9) and the body ministry that equips the saints (Eph. 4). Secondly, “Holy Places” encourage believers to form Christ-centred communities in any place, not just within a church building. Finally, “Holy Practices” see faith expressed in loving God and neighbours sacrificially, not in religious rituals and ceremonies.

Certain contemporary missiologists propose that a way forward in the West could be to adopt a hybrid model whereby churches adopt the most significant practices of CPMs/DMMs but remain pragmatic that inherited modes of church are deeply embedded. The focus should be upon raising up leaders and laity into mission, from within the existing church. They propose decentralizing the locus of power and authority within the local church and empowering all believers to adopt missional practices and to creatively contextualize the gospel, so as to create momentum towards missional movement.